Vegan versus Meat: Which is better?

Story by Larry Bartlett

Illustrations by Bailey Anderson

Have you watched The Game Changers on Netflix? Have you noticed that vegetable protein drinks are sometimes labeled as “clean protein?” Does this mean that meat protein is “dirty?” How does this affect us as hunters? How in the world did we even get to this juncture of pitting veggies against meat?

For thousands and thousands of years, no one really cared whether their food source consisted of a vegetable, meat, nut, fruit, etc. Instead, the primary concern was obtaining sufficient quantities of nutrients for the cache and/or the ability to follow food resources. Entire civilizations of hunter/gatherers were mobile by design, expending great amounts of energy as they tracked the animal migrations that sustained them. A recent comprehensive review of over 150 scientific studies concluded that the saturation of highly processed foods in our diets and lack of physical activity in our lifestyles are likely the greatest health nemeses of modern times, not whether or not we eat meat. As hunters, we consume as much wild fish and game as possible, and must expend energy to do so. How did our society get to this point of demonizing meat consumption, and how does vegetable protein really compare?

The Agricultural Revolution dramatically reduced the incidence of hunger and starvation, and the Industrial Revolution ushered in a greater convenience of foods. However, with these periods of positive changes also came negative repercussions: The intake of processed foods and unhealthy, saturated fats increased. To complicate measures, physical activity declined greatly in the last two generations due to the onset of the Digital Age. As these changes from the ancient, pre-determined genetics of our hunter/gatherer ancestors have occurred in a relatively short period over our recent evolutionary time scale, humans have not had time to properly adapt genetically, and we are paying the price with increased incidence of chronic disease. Most people are aware of these modern risks, but continue to consume unhealthy foods from their recliners while glued to the TV, phone, tablet or computer. As hunters, we continue to fight against modern influences. We strive to make connections to our ancestors, food, and families through our hunting lifestyles.

Many critics of the hunter’s fare argue that red meat in particular may not be good for us, and instead push intake of only vegetables. Most folks realize that commercial meats may contain excessive amounts of saturated fats, which have been directly linked to an increased risk of metabolic diseases. This is a prime example of the importance of individual macronutrients in meats, especially the protein and fat types and contents. Unless they benefit from hunted game, Americans eat more 70% lean/30% fat (70/30) ground beef than any other commercial meat. Almost 50% of the fat in 70/30 beef is saturated fat, and it contains only 0.01 grams of polyunsaturated fat (the “good for us” PUFAs). We need almost 100 times more PUFAs than saturated fats to offset the risks of metabolic disease in our westernized societies. Fortunately for the hunter, wild game is much lower in saturated fats and higher in PUFAs.

What are PUFAs? There are three kinds: eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acids (DHA), which are more beneficial than alpha linoleic acid (ALA) in reducing the risk of heart disease, diabetes, and even cancer. This is due to the favorable influence of EPA and DHA on the health of our blood. While commercial meats are largely devoid of these helpful EPAs and DHAs, many people recognize that salmon and other coldwater seafood are great sources of these nutrients. Many do not realize, however, that red meats harvested by the hunter, from caribou and other truly wild ungulates, contain large amounts of the beneficial DHA. This is not entirely surprising, given that indigenous populations of hunter/gatherers living in northern latitudes and consuming high DHA protein sources for millennia, have a low incidence of metabolic disease despite a marginal intake of vegetables. It should begin to be apparent that not all fats are bad fats, and the devil is in the details when it comes to dietary intake. It is far more complex than the demonization of red meat, especially red meat obtained through hunting, and the glorification of vegetables.

DHA and EPA go beyond their anti-inflammatory influences. These fatty acids also synergize with dietary proteins to remodel our muscle, which is in a constant state of breakdown and synthesis. Beyond this, specific amino acid profiles found in animal proteins such as eggs, milk, fish, and yes…even red meat, activate our muscles to rebuild themselves through initiating muscle synthesis. Sheri Coker’s research as part of her PhD program at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, recently demonstrated the superior influence of free-range reindeer compared to commercial beef. Reindeer is comparable in fatty acid and amino acid profiles to caribou, a prominent source of protein for Alaska hunters. This is the first known study to provide definitive evidence of immediate, cause-and-effect health benefits of free-range red meats on protein metabolism in humans. Free-range reindeer, comparable to wild caribou in fatty and amino acid profiles, provided a near 50% greater net protein balance and significantly higher blood concentrations of certain important amino acids (compared to commercial beef). Inherent differences in fatty acid/amino acid profiles between free-range and commercial meats are most likely responsible. We would anticipate even more remarkable differences when wild, free-range meat proteins are compared to vegetable proteins. Plant protein quality, especially regarding the ability to stimulate muscle synthesis, is subpar. Oddly, while we may all understand differences in the quality of carbohydrates (simple versus complex), public comprehension of protein quality is lagging.

There must be a reason these wild red meats eaten by the hunter manifest with different profiles from commercial meats. The widespread use of feed lots has not only increased the amount of saturated fats in commercial meats, but it has also increased the proportion of omega-6 (pro-inflammatory)/omega-3(anti-inflammatory) fatty acids. How did this happen? Just think about it and the answer becomes obvious. Wild grasses and leaves contain substantial amounts of healthy omega-3 fatty acids and phytosterols. Wild game must work hard to obtain their food sources, and after consumption, these nutrients are transferred to their muscle, or the meat we consume as hunters. Alternately, corn or grain contains minimal omega-3 fatty acids or phytonutrients. Unlike the roaming, range-fed wild animal harvested by the hunter, these nutrients can be consumed with little to no effort on the part of the animal. This increases the total fat in the animal’s muscle, and lessens the nutritional benefits from the commercially-derived meats—so nutritionally different from hunted, wild red meats.

Even the most stringent hunter-gatherers were omnivores, eating both plants and meat, and this is quite different than consuming only vegetables. For one thing, many plant proteins are not complete. This means they do not contain all of the essential amino acids. EAAs cannot be made by the body and therefore these EAAs must be consumed in the diet. Plant proteins like buckwheat, quinoa, and soy are complete, but are not as robust when it comes to muscle synthesis. Researchers compared two hunter-gatherer tribes in Tanzania: those following an omnivore diet, and those who ate vegetables only. The omnivores had lower blood pressures and blood lipid levels, indicative of lower chronic disease risks.

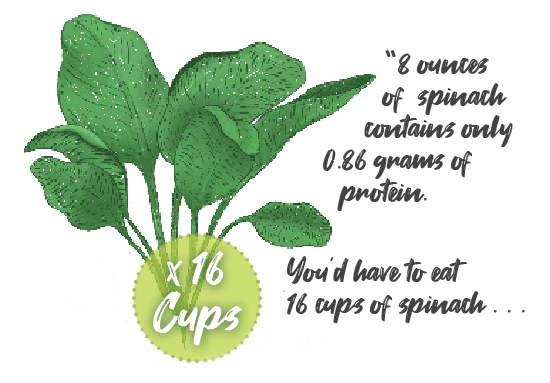

We must also examine the benefits of hunted meat protein over vegetables. In other words, how much energy can we obtain per given weight from meat versus vegetable protein? Most vegan or non-meat foods contain only 20–60% of the protein density found in meat! While spinach might contain protein and EAAs, 8 ounces of spinach contains only 0.86 grams of protein. You’d have to eat 16 cups of spinach to equal the 51.5 grams of protein found in 8 ounces of wild, hunted caribou. The time it would take to chew that cud alone would be overwhelming, but then you add the digestibility factor, you certainly recognize the absurdity of the comparison.

Finally, if you want to consume wild red meat for reasons of health, avoid feeding the wild animal processed foods, corn, or other foods with a high glycemic index. Doing so negates the potential for optimal benefits due to outside environmental manipulation. The food of the animal and its effort to obtain it eventually shows up in the meat you consume. Here, it may have more or less benefit for you as a hunter.

We often find that the narrative surrounding vegan versus meat protein, and any judgment of hunters for our chosen lifestyle, has been oversimplified. This is absolutely the case when it comes to the negative image of hunted, wild red meat in the eyes of the nay-sayer. Not all red meat is created equal, or exists in an equivalent environment. It is not rocket science but it is science. Our non-dramatized knowledge of science without media dramatization is our best weapon to defend our hunting culture against negative public opinion and chronic disease.

Scientifically, hunted, wild red meat is superior to both commercial meats and vegetable protein.

Larry Bartlett is the owner of Pristine Ventures based in Fairbanks, Alaska, and is an avid, hardcore outdoorsman. Pristine Ventures offers a slew of resources for backcountry hunters and fishermen like selling top-quality packrafts and canoes that can hold loads needed for outdoor activities. Larry also helps plan hunts for DIY hunters and provides equipment rentals.