How to care for your trophy in the field in Alaska

It has finally happened. The animal you’ve dreamed about taking is lying on the ground. Now what? If you’re not prepared, you could ruin that taxidermy trophy of a lifetime. Whether it’s a 70-inch bull moose, your child’s first black bear, or a King Eider on St. Paul Island, knowing how to care for that animal before it gets to the taxidermist matters. It can be the difference between a quality mount to enjoy for a lifetime or a disappointing story of it going to waste.

© Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Wild Reflections

-

-

© Potter’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Naturally Wild Taxidermy

-

-

© Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

View Photo Gallery

by Garry Greenwalt

We’ve talked to some top taxidermists across Alaska including Samantha Ball of Naturally Wild Taxidermy, Grant Gullicks of Wild Reflections, Jesse Dahlberg of Dahlberg’s Taxidermy, Dave Gum of Caribou Ridge Taxidermy, and Matt Potter of Potter’s Taxidermy for their insight on field care for your trophy so you’ll be able to honor that animal and relive those memories long after the hunt is over.

Common Big-Game Field-Care Mistakes to Avoid

All of our experts agree that the biggest mistakes they see year in and year out are a simple lack of knowledge of proper skinning techniques and field care. These mistakes are easy to avoid with some simple preseason preparation.

Read more...

Jesse Dahlberg, Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

“There are a few specific mistakes I see consistently. A big one is guys cutting off part of the ears when removing the skull from a bear hide. It is important to understand where the ear canal is on a bear and follow the skull when making your cuts to separate the skull from the hide. Another big mistake is cutting the back edge of the eyelids when capeing animals out. I see it a lot on moose and caribou. Take your time around these areas and make sure you’re leaving enough skin to work with. Lastly, make sure you leave the cape long enough with at least six to eight inches of hide behind the armpit area; more is even better.”

Samantha Ball, Naturally Wild Taxidermy

“The worst mistake is failing to research and learn proper techniques prior to harvesting your animal. Improper handling will result in unmountable hides due to hair slippage from bacterial growth. Give your taxidermist a call prior to going on your hunt. If you are unsure of skinning, fleshing, or salting techniques make an appointment to stop by a shop and learn.”

Grant Gullicks, Wild Reflections

“There are three common mistakes. The most common mistake is salting hides without proper fleshing and turning. This dries the meat and fat on the outside, but does not allow the salt to penetrate deep enough to absorb the body fluids close to the skin itself resulting in hair falling out in patches after the skin has spoiled. The second is salting the hide and placing it in the freezer right away before the skin has a chance to properly dry. Think of it as the difference between the freezing temperatures of saltwater versus freshwater. Saltwater has to get much colder than freshwater in order to freeze. When hides are salted and put in a freezer it keeps the body fluids in a liquid state and does not allow the hide to freeze or dry resulting in damage or complete loss of the hide. The third mistake is poor field care, which almost always results in damaged hides or complete losses.”

How to Deal with Warm Weather and Remote Locations

Remote locations and warm weather can present some serious challenges for hunters trying to preserve trophies in the field. All of our taxidermists agree that knowing how to split lips and noses, turn ears and proper application of salt is crucial.

Read more...

To properly salt a hide, it must have the ears turned, the lips, nose, and eyelids split, and all flesh and fat removed. Lay the hide raw side up and thoroughly rub salt into every square inch of hide. Fold the cape flesh to flesh and roll it up, then prop it up at an angle so the fluids drawn out by the salt can drain away from the hide. A cape may require 10-25 lbs of salt depending on the size of the animal. An entire hide may require 50 lbs or more. Hauling in that amount of salt isn’t always practical or possible.

Using a citric acid mix is another alternative to extend handling time. Using citric acid is really quite simple and is available in concentrated powder form in a product from Indian Valley Meats called Game Saver. It is mixed with water and sprayed onto the hide and meat. The biological complexities of how and why it works are material for another article, but to put things in a nutshell, it lowers the surface pH and prevents the growth of bacteria and helps keep insects at bay. The ears need to be turned and the lips, nose, and eyelids need to be split prior to application. To apply it, mix the powder with the appropriate amount of water and spray it liberally onto the flesh side of the hide. Make no mistake, citric acid is not a substitute for good field care practices and is only a tool for extending the handling time of hides and meat. Keeping things as cool, dry, and clean as possible and getting them out of the field in a timely fashion is still the best bet. For an in-depth explanation of citric acid use, check out this article by Larry Bartlett of Pristine Ventures.

Grant Gullicks, Wild Reflections

“Warm weather and remote situations are what we do here in Alaska, but it can be very tricky to keep your trophies in good condition. The golden rules for hide care in the field are similar to meat care. Keep hides cool and dry. Another item I highly recommend is food-grade citric acid, the same stuff you use to spray your meat. No one is going to backpack 10 pounds of salt on a sheep hunt, which is where citric acid comes in. It weighs almost nothing, helps prevent bacterial growth and extends the life of your hides in the field, allowing you more time to get them out of the field and properly cared for.”

David Gum, Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

“Keep the hide, cape, rack (especially velvet racks), and your meat in a cool dry place. Utilize game bags and cover them with a tarp if it is raining. Do not allow these items to sit in the direct sunlight and become dried out. If it is extremely hot out, you can put these items in a water tight bag, tie a rope to it, and submerge in a creek or lake to cool them down. In the evening, you can lay them out or hang them, so the nighttime temps can keep them cool. You can drape hides over a bush, this allows airflow over the hair and raw sides. If you are going to be out in the field for more than 24- to 48- hours after taking an animal, I advise you to remove the skull from the cape, as well as the paws or hoove bones if needed, and start fleshing the hide or cape, then turn the ears, split the lips, eye skin, and nostrils. If you don’t have salt, dry out the hide or cape as best you can after this work is done.”

Proper Big-Game Skinning Techniques

It is imperative that you learn proper skinning techniques and the associated cuts. If you are new to the game or not entirely comfortable with it, go visit a taxidermy shop for guidance. Pack a how-to skinning guide with you in the field for quick reference. Watch some videos. These are essential skills for any hunter to have.

Read more...

Matt Potter, Potter’s Taxidermy

“I prefer a belly (or flat) cut for rugs and lifesize mounts. This cut gives you more options and tends to be easier to work with on the form. Keeping the cuts centered and clean are key. On shoulder mounts, I prefer the animals to be tubed out, using only a small incision to remove the cape from the skull if at all possible. On small game, just bring it in whole or tube it out if you know how. The most important thing is to take the time to do a good job, even when you’re tired or in a hurry. One thing I suggest is to practice the different skinning techniques,even when you don’t plan to have the animal mounted, that way when the time comes you are more comfortable with what you need to do. Above all else, follow your taxidermist’s advice!”

Samantha Ball, Naturally Wild Taxidermy

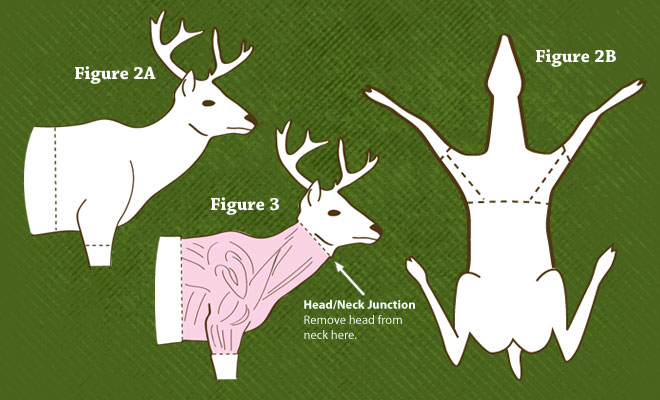

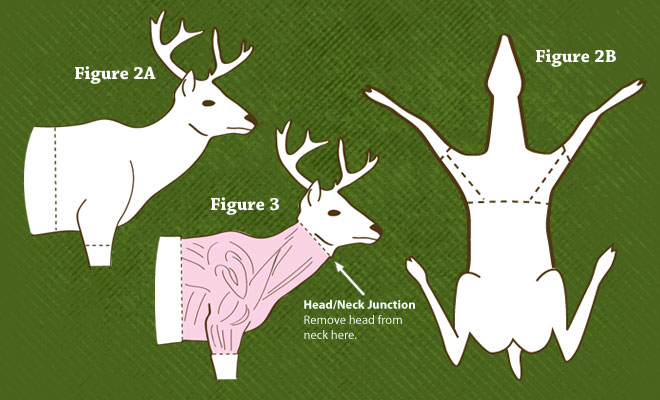

For a shoulder mount: Make an incision into the hide using a sharp knife. Circle the body behind the shoulder at approximately the mid-way point of the rib cage behind the front legs. Slit the skin around the legs just above the knees. An additional slit will be needed from the back of the leg and joining the body cut behind the legs. Peel the skin forward up to the ears and jaw exposing the head/neck junction. Cut into the neck approximately three inches down from this junction. Circle the neck cutting down to the spinal column. After this, cut the head off the neck. This should allow the hide to be rolled up and put in a freezer until transported to your taxidermist.

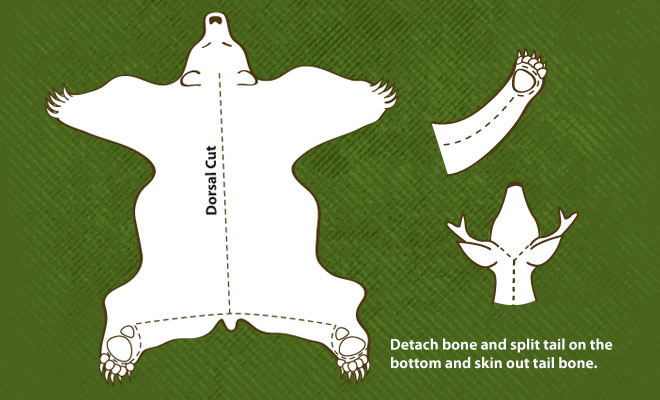

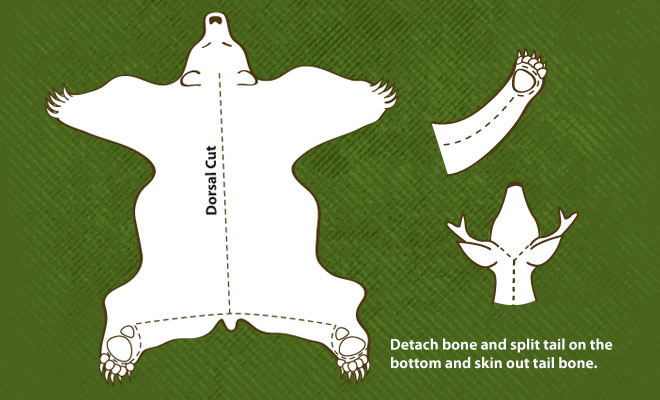

For a life-size mount: There are two methods of skinning for a large, life-size mount like deer, elk, or bear for taxidermy. These methods are the the dorsal method and the flat incision.

The Dorsal Method is recommended for most life-size mounts which involves a long incision down the back (from the base of the tail up to the back of the head). Then the hide can be peeled off the carcass through the incision. Skin down the legs and cut the legs but leave the foot/hoof and skull for your taxidermist to remove. Freeze it or take it to your taxidermist as soon as possible. If you will remain in the field, learn to properly remove the head and feet/hoofs to prevent hair slippage. Then follow proper salting methods.

For a rug mount and some life-size mounts, we recommend the flat incision. The area to cut is shown in Figure #1. Make these slits (cutting the feet free from the carcass). The head should be detached in the same manner as the shoulder mount.

Small Mammal Field Care

Coyote-sized or smaller animals should not be skinned unless by a taxidermist. Don’t gut the animal, either. Small mammals, especially carnivores, will spoil quickly because of their thin hide and bacteria. Call your taxidermist to schedule a time to drop off any small game animal. As soon as the carcass cools completely, put it in a plastic bag and freeze it.

How to Take Care of Birds in the Field

Birds are relatively easy to take care of in the field, but there are still some common mistakes that you need to avoid and steps to take to ensure you get a quality trophy back.

Read more...

Matt Potter, Potter’s Taxidermy

Birds are one of Matt Potter’s specialties. If you’ve visited the Anchorage Cabela’s and seen the sea ducks and habitat over in the fishing area, then you’ve seen some of Matt’s work. Matt says, “Get away from the old panty hose trick for storing the birds in the field and at home. The nylon material is abrasive and damages the outer parts of the feathers plus it has a tendency to dull the iridescence. My advice is to clean off as much blood as possible without getting the bird too wet. If bleeding continues, use tissue paper to block the throat and nasal passages. Allow the bird to cool down. Wrap the bird in a plastic bag and remove as much air as possible, then wrap it in second bag and freeze it if you can’t bring it in right away. Birds stored in this manner can last a long time.” Matt says when deciding on a bird to mount, stick with prime specimens. Birds shot later in the season (no earlier than mid-October) have far better plumage and make much nicer trophies. One thing he really likes his clients to do is bring in a picture of the pose you want and the habitat you like. It makes things much easier on him!

Samantha Ball, Naturally Wild Taxidermy

“Do not gut the bird. Cool the bird immediately to prevent feather loss. Rinse any blood from the feathers with water. Schedule a time to drop the bird off to your taxidermist the same day or freeze it. When freezing, place the bird into a plastic bag and remove excess air. Be sure not to damage feathers. Leave the tail feathers sticking out of the bag if necessary.”

The Best Knives for Field Care

Our experts’ answers on the best knives were pretty unanimous.

Read more...

Jesse Dahlberg, Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

I use a variety of blades and handles from Havel’s, Inc. for both field and shop work. For the bigger field chores I prefer my Bolduc knife. It’s well made, holds an edge, and won’t rust.

Grant Gullicks, Wild Reflections

“I always carry a disposable blade knife with me. They are razor sharp and capable of taking apart an entire animal, as well as fleshing, turning, and other field-care chores. On hunts where weight is an issue I will only carry a Tyto knife with 6-10 blades. Other popular replaceable blade knives are the Havalons.”

Matt Potter, Potter’s Taxidermy

“Stick with any knife you are comfortable with. Get a good quality blade that you like and use that for all of your general field care and skinning chores. I prefer Havalon for the finer detail work around the face.”

David Gum, Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

“The items I carry and utilize on a daily basis are a Havalon knife, #22 blades, game bags, a small fixed blade knife with a sharp blade, a 6×8 tarp, the smallest amount of salt required (if needed), a carabiner with paracord and halibut hooks with the barbs and tips ground down that I utilize for skinning, and mainly pulling out bear paws and hooves.”

Samantha Ball, Naturally Wild Taxidermy

“For most of my skinning and prep work (ie: turning ears, nose, and splitting lips) I use a Havalon Piranta Edge with replaceable #60A blades. When in the field, a sharp knife that you are comfortable with is a must for eliminating unnecessary holes and making straight, precise incisions.”

[Also: Check out our Editors’ Choice Awards for more Hunt Alaska gear favorites.]

How to Preserve Velvet

Velvet-covered antlers can be a nightmare to deal with. They are delicate and preserving the thin tissue is time sensitive. Follow the advice below to give you the best chance at preserving the velvet, but keep in the mind there is always the synthetic option.

Read more...

Jesse Dahlberg, Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

“It’s pretty simple, keep velvet-covered antlers cool, dry, and covered up. Covering them with a game bag will help keep the flies off and prevent a maggot infestation. If you can get them to a freezer, great. If you can get them to me right away or another taxidermist who is equipped to handle them, that is even better. I have several tanks full of a proprietary solution to preserve the velvet in its natural state and the finished product is extremely durable. I have one caribou with velvet that I mounted in 2001 that has literally traveled around the world with me and is still in perfect shape.”

David Gum, Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

“When taking an animal with velvet antlers, it is important to keep the rack cool and dry. You can use a needle to poke holes in the antler tips and the base of the antlers, then put the rack upside down and allow blood to drain. Keep a breathable game bag over each antler. Do not allow flies to land on the antlers. They are attracted by the blood and will lay eggs and then you will have maggot issues. Typically, velvet moose and caribou will start to strip their velvet between August 26th to September 5th. Animals taken before this time may have underdeveloped antlers with soft tips. If the antler tips are rounded and mushy to the touch they are not fully grown and it is a good idea not to strip the velvet. You will be left with a bloody nub and sometimes a piece of the antler will fall off. Bring the velvet antlers to your taxidermist as soon as possible. If you have a freezer available, you can freeze the rack. If the rack is too big for the freezer, split the rack down the middle of the skull plate. Freezing doesn’t preserve the velvet, but is does stop if from rotting. When time permits, bring the frozen rack to your taxidermist for antler preservation.”

Grant Gullicks, Wild Reflections

“Velvet is difficult to preserve without the right training and tools. It is fragile and spoils extremely fast. The absolute best thing you can do is keep the velvet cool and get it to me very quickly. It is not usually feasible to bring the chemicals and tools into the field needed to preserve velvet. A general rule of thumb is if it feels loose and slides on the antlers then the best option at that point is to strip the velvet as it has already released from the bone and is highly unlikely to preserve.”

General Taxidermy Advice

We asked each of our top taxidermists for one last piece of advice they’d give our readers before heading out into the field.

Read more...

Jesse Dahlberg, Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

“Keep things cool and dry, that is the key. Learn how to properly prepare a hide for salt and use it if the conditions call for it. Once you have a hide salted and rolled up, prop it up at an angle so the fluids and moisture can drain away from the hide.

Samantha Ball, Naturally Wild Taxidermy

“Do your research prior to your hunt and get in touch with a taxidermist. Know what kind of mount you want. We can make recommendations based on hair quality, size, etc. but have ideas in mind before you start making incisions. Always bring more hide to your taxidermist as we can always cut off the excess. Taxidermists are skilled professionals but we are not magicians!”

Grant Gullicks, Wild Reflections

“I am always happy to show my clients tips and pointers in person. I have made an in-depth field care guide containing skinning cuts, field care, and tool recommendations that I have presented at the Wild Sheep Foundation Banquet several times at the Sheep Hunter University. It is available for anyone under the Trophy Care page of my studio’s website or follow this link.”

Matt Potter, Potter’s Taxidermy

“When you get your animal, take good field pictures of it and the surrounding habitat as well. When you go into your taxidermist, having an idea of want you want and being able to show them pictures or other reference material is priceless. Knowing what pose you want or even better, the exact form you want your animal mounted on, makes it easier for a taxidermist to produce a mount you’ll be happy with. The bottom line is, don’t make your taxidermist guess or read your mind. Keep in mind that an animal’s coat changes throughout the season and how one animal looks in a picture is not necessarily how your critter is going to look once it is completed. Winter hair is much longer and thicker and can make an animal look bigger than it would with an early fall coat.”

David Gum, Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

“Use common sense. Think about the cuts you are making before you make them. A lot of time, money, and effort are put into hunts, and to me every animal taken is food for the table and a trophy—no matter the size. Don’t waste all of that by making bad cuts, or letting trophies rot. Ask your taxidermist for skinning and field care tips prior to going hunting. I give free skinning- and field-care classes to individual hunters or groups year ‘round for any game you will be hunting or might come across on your hunts. If you are in the field, don’t hesitate to get a hold of your taxidermist if you have questions. Hunters contact me from the field via satellite phones, Garmin inReach devices, and cell phones to ask questions all the time. I walk them through step-by-step directions to care for the game they have taken.”

How-to Videos and Other Reference Materials

Meet Alaska’s Top Taxidermists

Special thanks to Hunt Alaska’s Top Taxidermists for their tips and advice to produce the best-looking trophy for your memories.

Jesse Dahlberg, Dahlberg’s Taxidermy, Wasilla, AK – WEBSITE

Born and raised in Minnesota, Jesse Dahlberg joined the service in ‘92, retiring 20 years later in 2012. Taxidermy started out as a hobby for Jesse then turned into a profession in 2009. Jesse started Dahlberg’s Taxidermy in April of 2009 out of a three-car garage but it soon grew and moved to Wasilla where he operates out of a 3500 square foot facility attached to his house for security purposes. Having his shop attached to the house is nice for security but it is hard for Jesse to stop working sometimes until 11 PM most days, or even 1 to 2 AM some days. Jesse employs two people full time that flesh, turn, salt, etc. He is self taught and says he does the best he can and strives to get better each day. Take a look at Jesse’s work. “The best he can” is pretty darned excellent.

Dave Gum, Caribou Ridge Taxidermy, North Pole, AK – WEBSITE

I was born in Fairfax, Virginia. I joined the Air Force when I was 19, and was a Military Working Dog Handler. I have always loved hunting, and have wanted to be a taxidermist since I was a young teenager. I moved to Alaska in 2007 and once I got here I never wanted to leave! After serving in the Military, I spent a year In Afghanistan working as a Kennel Master on a civilian contract. I then put everything I had into my dream and opened my business in 2013. I love taxidermy and everything involved with it. Everyday is different and I enjoy the the time the hunters walk in my shop. I love listening to their hunting stories and seeing the animals they bring in, all the way to handing over the finished product and seeing the smile on the customer’s face when they pick up their mount.

Matt Potter, Potter’s Taxidermy, Soldotna, AK – WEBSITE

Matt started his taxidermy career at the ripe old age of 14, mounting a chukar from a neighbor’s game farm. After graduating high school he attended Mountain Valley Taxidermy School in Phoenix, Arizona, graduating in 1982. After working for a number of different studios in California and Nevada, he took a five-year break from the industry. Matt picked it back up about 15 years ago in Soldotna doing mostly bird and mammals on a part-time basis. Matt has competed and placed at the national level multiple times. 2018 will mark his first season operating his business in a full-time capacity.

Grant Gullicks, Wild Reflections, Chugiak, AK – WEBSITE

From a young age, Grant was passionate about the outdoors, fishing and hunting with his father at every opportunity and enjoying all that the Midwest has to offer. That passion for the outdoors and animals ultimately fostered an interest in taxidermy for Grant. He began working in taxidermy while still in high school. He expanded on that training during his college years by studying habitat recreation, animal physiology and anatomy, all while using his taxidermy skills to pay his way. Beginning his career at such a young age offered him opportunities to work and train with some of the top taxidermists in the industry, including the world-famous Animal Artistry studio in Reno, Nevada.

Grant’s passion for the outdoors still runs deep and the pull to Alaska could not be ignored. For the last eight years he has called the Anchorage area home, establishing his custom studio, Wild Reflections, with a reputation for truly exceptional and unique mounts of Alaskan species. His passion for perfection and realism is evident in every piece that leaves his studio, but sheep are his favorite subjects. He brings eighteen years of reputable experience, artistic vision and the ability to create a one of a kind piece that will capture the memory of your hunt perfectly.

Samantha Ball, Naturally Wild Taxidermy, Wasilla, AK – WEBSITE

I grew up hunting and fishing, and spending most weekends at our various hunting camps in the Adirondacks (upstate New York). I was very artistic from a young age and always curious about taxidermy. I learned preservation techniques and dabbled in small taxidermy projects while living in New York. I moved to Alaska 10 years ago and worked various jobs to save up enough money to start Naturally Wild Taxidermy. I attended The Artistic School of Taxidermy in Idaho where I specialized in Alaska Lifesize, shoulder mounts, birds, and fish. I have owned and operated the business full time for three years. Business continues to grow every year and we are excited to expand services to include African animals starting this year!

Photo Gallery

-

-

© Wild Reflections

-

-

© Wild Reflections

-

-

© Naturally Wild Taxidermy

-

-

© Naturally Wild Taxidermy

-

-

© Naturally Wild Taxidermy

-

-

© Naturally Wild Taxidermy

-

-

© Naturally Wild Taxidermy

-

-

© Naturally Wild Taxidermy

-

-

© Naturally Wild Taxidermy

-

-

© Naturally Wild Taxidermy

-

-

© Naturally Wild Taxidermy

-

-

© Naturally Wild Taxidermy

-

-

© Naturally Wild Taxidermy

-

-

© Naturally Wild Taxidermy

-

-

© Naturally Wild Taxidermy

-

-

-

© Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

-

-

© Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

-

-

© Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

-

-

© Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

-

-

© Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

-

-

© Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

-

-

© Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

-

-

© Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

-

-

© Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

-

-

© Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

-

-

© Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

-

-

© Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

-

-

© Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Wild Reflections

-

-

© Wild Reflections

-

-

© Wild Reflections

-

-

© Potter’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Potter’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Potter’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Potter’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Potter’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

-

-

-

© Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

-

-

-

© Naturally Wild Taxidermy

-

-

© Naturally Wild Taxidermy

-

-

© Naturally Wild Taxidermy

-

-

© Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

-

-

-

© Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

-

-

© Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

-

-

© Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

-

-

© Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

-

-

© Caribou Ridge Taxidermy

-

-

© Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Dahlberg’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Naturally Wild Taxidermy

-

-

© Potter’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Potter’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Potter’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Potter’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Potter’s Taxidermy

-

-

© Potter’s Taxidermy